- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

The year is 2009. Shah Rukh Khan, the popularly dubbed King of Romance, has already started dabbling in films that no longer follow the Yash Raj rom-com template. Bollywood and Hindi Cinema as people know it has started to change, a change that is exciting and yet unfamiliar. Dharma Productions has just about started developing the formula for a certain kind of mainstream cinema, that would use the template of a song and dance romance in exotic foreign locales to talk about issues of “graver importance”. In this situation, the country is suddenly presented with a coming-of-age romance starring one of the most unconventional pairings in Bollywood till then. Ranbir Kapoor, the son of Neetu Singh and Rishi Kapoor, and art-house darling Konkona Sen Sharma, daughter of another art-house actress-director legend Aparna Sen. Not only were the actors from different cultural and geographic backgrounds, but the age difference between the two was unmistakable. Bollywood was finally willing to look at the possibility of a romance between an older woman and a younger man. Ayan Mukerji is a director-writer no one has heard of before, who people will later come to spot in the closing shots of 'Tumhi Dekho Na' from Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006) dressed in a ripe green jumper. Yet the result is a film that will most definitely be on its way to becoming an enduring classic in the canons of Bollywood.

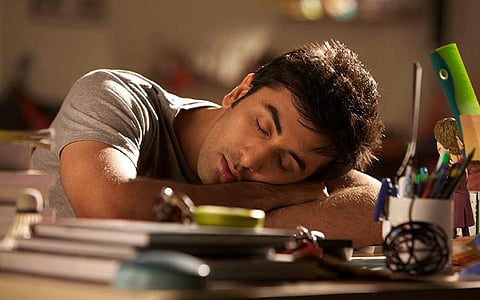

Wake Up Sid, to date remains one of the most talked about films of the last two decades. It took the story of a young, spoiled Bandra boy and infused in it the layers, textures, and moods that people had stopped expecting from the urban romantic drama for a while. Although the age difference in the romance of this film was not as staggering a thematic concern as seen in Dil Chahta Hai (2001), it nonetheless brought back quietly to the mainstream foray something that has been considered taboo for the longest time in urban social circles. The director himself has commented on the “safe” nature of the writing, which in an attempt to retain the simplicity and innocence of the story at hand, denied the narrative any space to delve into the complexity of any possible sexual tension between the lead pairs. Although a leading production house like Dharma did take the decision of foregrounding a leading romance with an age difference in a commercial film, it was going to be a while before the sexual potential of the same was going to be explored. Suddenly Ranbir Kapoor was not just a fantasy lover boy from the blue world of an eccentric artiste. He was the boy next door. We all knew him. He read comics, he carried around a camera with no clue about his actual talent at noticing and capturing frames. He took his money for granted. He had no clue what he wanted from his life. Ranbir Kapoor’s Sid was finally the portrait of a generation of young boys and girls in urban city spaces. They were no longer men and women who were expected to uphold their family's traditions and join the business. These were boys and girls who did not know what to do with their lives simply because they never had to spare a single thought about what to do the next waking day.

The film also gave us the gift of Aisha Banerjee. In a role that came right on the heels of her deeply meta performance in Luck By Chance (2009), Sen Sharma took the trope of the manic pixie dream girl and built a character that was full of flesh and blood. Her Aisha, despite being a seminal catalyst in making our young man-child realise supremely important life lessons, was also a woman who harboured dreams of making it in the big city. In many ways, despite being a wake-up call for Sid, the film was truly Aisha’s relationship with the City of Dreams. For the first time, a Dharma film entered the space of a relatively small apartment in Bombay. We saw a sequence of two strangers, on the verge of romance, setting up their corner in a world that continued cruelly around them. They stole moments on the terrace and shared life, their deepest desires and vulnerabilities with each other as the looming cityscape watched over them - sometimes heaving a sigh at their naivety but never threatening to crush their burgeoning dreams.

But the reason why this film worked then, and continues to work even today is not just the romance of these two characters. For a generation that grew up in the wake of globalisation, our on-screen heroes and heroines finally became people who challenged the very codes of masculinity that had been fed to us for years on end. Kapoor was not a macho man who had any intention of fulfilling his familial expectations. He was someone who got a seat in a college because he comes from money (what does the nepo-debate make of that is a question to consider). He walked out of his family, for all the wrong reasons, and embarked on a journey to find a semblance of home somewhere out there in the big world. An often overlooked aspect of this film is the way it explores the relationship that outsiders share with the big cities they come to. As an outstation student studying in the capital of the country, it is a part of my experiential reality to know how not-so-smooth a ride living alone is. There are rents to be paid, food to be cooked and a sanity to be seeked in the small room you find yourself in when the day comes to an end. But even amidst the brouhaha of the do-or-die situation our cities place us in, there is always a soft spot that we harbour for it. Despite all the times that mirage is shattered, we continue to yearn for our Bombay to be soaked in rain while our hearts ache for lovers of the past and our hands hold our hundredth cup of piping chai.

It is with the success of this film that Bollywood unleashed upon us an entire sub-genre of coming-of-age films that began to surreptitiously look at leading men who were essentially rootless. Yet again in 2013, Ayan Mukerji returned with his second feature, starring Ranbir Kapoor paired with Deepika Padukone this time. Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani is often termed to have done to this generation, what Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) did to the preceding generation. If his Sid was a man who walked out on a rich father to find his own in the big city, Kapoor’s Bunny was another man-child who despite his upper-middle class lineage had no intention of ever finding himself a home. At several points in the film, he says out loud that he wants to travel the world non-stop. He carries with him a notebook, with handwritten names of places across the world he hopes to visit someday. Funnily, he is a photographer in this film as well.

But his desire to travel comes at the cost of all the relationships he holds. If Wake Up Sid shows Bombay as a space, with its thousand intersecting trains and choked-up streets, which offers a tiny rain-drenched corner to two young yearning lovers, Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani showed us the cruelty that lurks in the spaces we often invest our greatest dreams in. Manali is where Bunny falls in love, but it is also where he encounters his first heartbreak - one that he very conveniently suppresses. The montage we see in Ilahi shows us the glamorous hippie life Bunny always yearned for, but the final shots of the sequence also show us a lorn Bunny sitting atop a moving vehicle, his many cameras in place. Even as his cameras capture the colours of Paris on the very cusp of life, the director’s gaze captures for us Bunny’s lifelessness. But his rootlessness comes even more exacerbated in the final moments of the 'Kabira' song sequence when Padukone’s Naina catches him welling up as Kalki Koechlin's Aditi completes her marriage vows. Caught off guard, Bunny tries to hide away but Naina’s knowing smile breaks him, as he proceeds to make one final exit - paying the heavy cost for his rootless dreams.

Ranbir’s urban bourgeoise characters also harked back to the concerns of our classical heroes - but this time around, in the face of rising concerns of cultural violence being faced by millions of global, yet largely rootless immigrants. These films, which incidentally come in the wake of the 2008 global economic crisis, pointed to the making of yet another generation of movers and shakers who were not scared of the travails of emotional displacement. Especially one that came at the cost of a dissonating physical displacement across the borders of cities and countries. The West was only a contingent location, a promise of sorts. The final point of arrival however almost becomes secondary to the process of the arrival itself. Moreover, it is the need for this arrival - only made possible through a literal and metaphoric displacement - that brings about an eventual realisation of the true self. This meant creating and destroying relationships constantly with the spaces that we come to inhabit around us. In Wake Up Sid, the home that Bombay offered Sid was a bubble that he must break himself to enter the larger urban isolation that the city offers to its outsiders. It is through seeing the city as the peering force of cruelty and loneliness, that it is possible for Sid to finally reintegrate himself within the fabric of the city, and find a home in it. Similarly for Bunny, the realisation of his true self comes not only through his interaction with Naina but also through his recalibration of the relationship he shares with the spaces around him. The mountains bring him heartbreak (the implausibility of a future with Naina and the news of a parent's passing), the urban metropolis of Paris brings him isolation and even more loneliness, while the streets of Jaipur, away from his hometown yet in closer proximity to his roots makes him realise the need to anchor himself even at the cost of chasing his dreams.

The geographic mobility of his self is given new heights in the third film Ranbir proceeded to do with Dharma Productions in 2015. This time directed by Karan Johar in Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, Kapoor essayed the role of Ayaan, an NRI in London. His fatal love for Alizeh brings him to Lucknow, a space where his violently aggressive claims to an unrequited love results in yet another exit from the country. But this time round, he finds himself not in London, but in Vienna where he comes to pursue the mysterious Urdu poetess Saba. It is here finally, a good half-decade after the release of Wake Up Sid that Dharma with its leading man Ranbir not only made an older-woman-younger-man romance a plot point, but also fully explored the deeply sexual nature of their shared relationship. Ayaan and Saba’s relationship was one that was sparked by an instant, unexplainable desire. While the two did find comfort of completely different natures in each other’s arms, the sexual passion was something that was made to stay in the foregrounding principles of their relationship.

When Ayaan’s pursuit of Saba doesn't lead to any fruition, he comes back to London as he emerges as a bruised singer. In this context, London becomes a negotiating space for conflicting desires. His desire for Alizeh and the much older Saba leads to a crossfire that is almost reminiscent of a singular tussle between two cultural extremes. In the end, he is grappling with a personality that embodies the contradictions of his desires which eventually comes to mirror the immigrant experience itself. It is most definitely an obsessive, overpowering passion - the kind which has caused the fall of our greatest literary heroes from Heathcliff in the moors to Gatsby in Upper East Egg. It is also a desirous passion we have seen on our screens - ardently portrayed by Shah Rukh himself in Devdas (2002) - where his unconsumate erotic desire triggers an immediate chain of self-destruction. Interestingly, in the climax of that film too, Devdas’s death is deferred till his travel and arrival at Paro’s mansion. But here, the desire mutates into an artistic output of sorts. The death drive doesn’t overpower the eros and there is no grand narrative of self-destruction. It is a settlement that he must come to terms with on his own and one that he will be able to make sense of through the aid of the art he produces.

In many ways, the three films, therefore, under the banner of Dharma Productions form nothing short of a spiritual trilogy. With Ranbir Kapoor, the scion of the Kapoor dynasty and the son of the formidable Rishi Kapoor himself, these films offered a new way of looking at the leading man in our movies. The motivations driving the man weren’t necessarily for purposes of exacting familial revenge. Cities, which had for the longest time been the keeper of desires, private and public, made us question the role they played in our stories, and Kapoor helped us arrive at the answers.