- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- Reviews

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

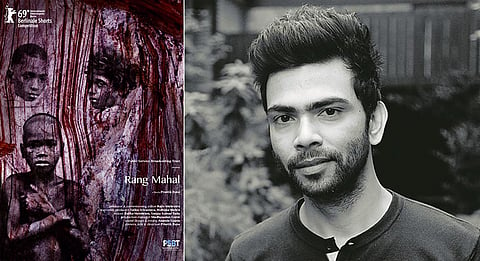

The only Indian film in competition at the Berlinale is Rang Mahal (Palace of Colour), directed by Prantik Basu. It's part of the Berlinale Shorts section, with a selection of 24 films from 17 countries. This is the theme: As a woman from the Santal community narrates a tale about the origin of creation, her village prepares for an annual ritual. This narration is important, because until recent years, the tribe did not have its own written language. Stories and myths were passed on orally through the generations. Each narration, therefore, takes on a different form, and the film represents this visually through the myriad hues of rocks in the nearby hills. This is the shape this particular narration takes: "This is an old story. In the beginning, there was only water. Deep, endless ocean, and darkness all around. Half-asleep, Thakur Jivi had a dream…" Here's the director, talking about his film.

"Now the sun sets here to rise somewhere else. But we are all a part of the same cosmic history." That's just beautiful. Where did you first hear about the Santal folk tales of Thakur Jivi and Marang Buru?

For the past few years, my filmmaking has been closely associated with the interpretation of folklore from different Indian regions. I find it fascinating how these primitive tales are often progressive in nature. They work as a time capsule. They offer access to our rich anecdotal history that is often lost in translation. While I was collaborating with the Santal community for another film, I read various versions of their Creation myths. That is when I came across the stories of Thakur Jivi, their local deity, and Marang Buru, the great mountain or the supreme being. But my film is not entirely based on them. It is more about the unique correlation of nature and culture, and an attempt to present a parable-like tale of an existing ecological art at the threshold of extinction.

The story being told is a fantastical one about the origin of creation, filled with swans and caterpillars. Can you talk about how you decided to juxtapose this narration with matter-of-fact visuals like men collecting soil or women walking with firewood bundles on their heads?

Depicting the fantastical with similar illustrative images would have left very little to the imagination. For me, the film does not play out on the screen, but projects itself on the mind of the viewer. Everyone views a film differently; it has a lot to do with one's individual memories and past associations. I like to keep my juxtapositions open to interpretations rather than imposing a similar inference for everyone. This way, I can offer a more engaging, participatory experience. If we look away from the urban rationale, we will find that these myths and legends are very deeply entwined in the everyday lives of the indigenous people. For them, a tree is not just a tree; a pond not a mere hole in the ground to hold water. They are often personified and associated with familial values. So I thought it would be more apt to look for traces of the fantastical in the mundane instead of exoticizing it with grandeur.

Who is the narrator, Balika Hembram? Where did you find her?

Balika Hembram is currently pursuing her PhD in Santali language at the Sidho Kanho Birsha University in Purulia. Sanjay Tudu, my friend from FTII and one of the collaborators on the film, knew her and suggested that we should meet her for the narration. Though this was her first time working on a film, I found exactly what I was looking for after just one voice rehearsal with her. I am grateful that she took time out for us.

The low, monotone-like voice she uses to tell the story — was that her natural style or your idea?

I would say it was a bit of both. Though on the surface, it might sound 'monotone like' to some, if one hears closely, there is a lot of drama in how she narrates the tale. She has modulated the intensity and intrigue in her voice according to the events of the story. But in most parts, I wanted to keep the tonality very conversational, as if a friend or a grandparent is telling a story.

You hold some shots for a long time. Like that of the face of a multi-hued rock, or the moon in the sky. How do you decide how long to hold a shot? Is it just instinct or something else?

How does one decide how long to hold a conversation with another person? Sometimes, a two-hour chat feels like two minutes while the same two minutes can feel like ages in some cases. It is about energies; how they match and how we tune in to them. While editing, I listen closely to the inherent rhythm of a particular shot. Only a certain fragment can bring it in sync with the overall duration of the film. It is like finding the right piece for the puzzle. It is a rather rigorous process, of trying out different permutations and combinations to find out exactly how long an image needs to stay on screen for the viewers to fathom the details that I hope they would perceive.

What made you not want to show the ritual as a "ritual", and depict it in a very casual (and non-explanatory) way. Towards the end, the shot even looks like abstract art.

The ritual is not what one sees at the end but the process of replenishing the houses in the village. It is a part of their annual routine where the men get the colourful clay from the hills while the women mend the cracks on the walls and paint them anew. "The house had grown" as they would say and it needs to be fixed, just like trimming the branches of a tree. So I did show the ritual, but chose a more 'matter-of-fact' tone in depicting it, instead of viewing it through an urban gaze towards tribal culture.