- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

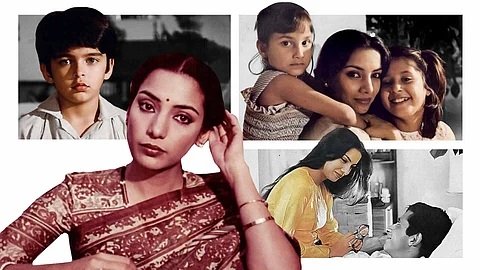

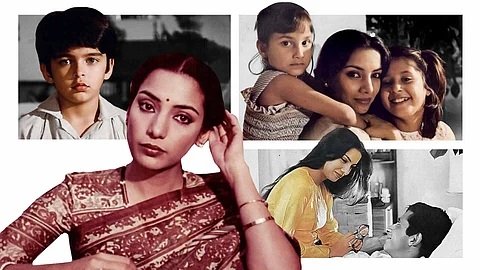

A little more than halfway through Masoom (1983), young Rahul (Jugal Hansraj) makes a jewellery box for Indu’s (Shabana Azmi) birthday. When she sees the handmade gift, Indu is overcome with surprise and pleasure. She reaches her hand out to cradle the boy’s face when her husband DK (Naseeruddin Shah) arrives at the scene — a harsh reminder that Rahul is the child of a woman with whom DK had an extramarital affair, and whose untimely death has brought Rahul to Indu’s doorstep. Indu swiftly draws back her hand. The smile drops from her face and she storms out without a word to Rahul, who is left heartbroken. In one simple scene, Masoom puts forth the complexities of Indu’s position as a stepmother: Her fury at her husband’s affair, her resentment towards her stepson warring with her grudging adoration of the young boy, her fear of a familiar family set-up changing forever, and her confusion at her own conflicting feelings.

The term ‘stepmother’ subconsciously evokes adjectives like ‘evil’ or ‘wicked’, thanks to the proliferation and continued relevance of European fairy tales across the world. From Lady Tremaine in Cinderella to the Evil Queen in Snow White, the stepmother is cruel, covetous and actively seeking to harm her stepchildren for selfish purposes. The Wicked Stepmother is one who has manipulated her way into a marriage, usurping the revered position of ‘Mother’ and abusing her power. Hindi cinema has also had its fair share of evil stepmothers: 1963’s Bahurani saw Lalita Pawar as a vicious woman who tortures her stepson and his wife, while favouring her biological son. In Raja Hindustani (1996), Archana Puransingh plays a woman who sabotages her stepdaughter’s marriage to get her hands on her husband’s wealth. Reema Lagoo’s character in Hum Saath-Saath Hain (1999) — her name is literally Mamta, which means ‘motherhood’ — is a little too easily influenced by malicious external forces, ousting her stepson from the household to make space for her children. Standing apart from all of these women is Indu, the mother and stepmother in Masoom.

Director Shekhar Kapur’s Masoom gently stretched the archetype of Stepmother to contain multitudes. Indu’s world is turned upside down when she discovers her husband had been unfaithful to her, and that she has to open her home to his illegitimate son. Indu’s initial treatment of Rahul verges on callous. She ignores his existence as much as she can, shutting down his attempts to connect with her and, on occasion, snapping at him for getting in her way. There are moments in which we see Indu letting her guard down — she often finds herself outside Rahul’s room despite herself, watching the boy sleep with a tender expression on her face, covering him up with a blanket. But the moment breaks when his past registers with her, and Indu withdraws, deliberately hardening her heart again.

It’s easy to paint Indu as a villain when she lashes out at a child for no fault of his own (especially one as adorable as a young Jugal Hansraj). But Azmi’s performance lends an interiority to Indu, never letting you lose sight of her profound hurt over her husband’s actions. It’s worth noting that while DK does apologise for cheating on Indu, it appears to come more from a place of regret that his past unexpectedly caught up to him years later. He places the onus of forgiveness and acceptance solely on Indu. Meanwhile, Azmi compels you to feel sympathetic to Indu’s plight. Her behaviour towards Rahul, difficult as it is to digest, feels justified. Indu’s careful distance from Rahul is a means to safeguard her peace, and perhaps the only way she sees to hold her husband accountable.

The stepmother in Masoom is as much a victim as her stepson. The film gives Indu the space to work through her emotions without imposing upon her an unconditional, unrealistic, maternal instinct. Indu forbids Rahul to call her ‘Mother’, demands that DK take him away, and rages at the child when he runs away from home. “Aren’t you ashamed? You are a guest in somebody’s house,” she rebukes him when Rahul finally returns. “We’re doing so much for you. Instead of being grateful, this is what you do,” she says. Then an interesting thing happens. With beautiful subtlety, Azmi pushes Indu’s tirade from a vicious rant that would widen the rift between Indu and Rahul into something more desperate. “I’ve been in and around the house searching for you. What would we have done if you’d been harmed in any way?” she says, tears flashing in her eyes. For a moment, Indu is transformed into a worried mother, a role that she’s refused to play for Rahul so far. Her anger acquires a tinge of distress as she paces back and forth. By the end of the film, Indu has made her decision. She may not have fully forgiven DK for his infidelity, but her love for Rahul eclipses every other feeling. Once she comes to terms with this, Indu wholeheartedly welcomes her stepson into her home.

Compelling and charismatic though she may be, the Wicked Stepmother is a reductive trope that fails to take into account the real concerns of blended families, focusing instead on the anxiety that a woman who is an outsider will tear the fabric of a family apart. It is an archetype that contributes to a myopic view of both maternity as well as femininity, with its insistence that a woman can only be a good mother if she has given birth. Being unable (or unwilling) to connect with a child is twisted into something spiteful, making the Stepmother a flat caricature, and refusing to give her the leeway to make mistakes or imagine a world outside the children in her life. Masoom adds nuance to the stereotype. Thanks to Shabana Azmi’s outstanding performance, the film shows us an Indian family that is held together by a woman (as per tradition), but one whose strength lies in moving beyond the narrow confines of stereotypical motherhood and stepmotherhood.

At one point in the film, Indu’s best friend Chanda (Tanuja) — a happily independent woman who eventually reconciles with her husband out of her love for her son — tells her, “A woman cannot stand firm when motherly feelings arise within her.” It’s a well-meaning if essentialist statement that speaks to a sense of inevitability in succumbing to motherhood. Indu’s anger at DK and reservations towards Rahul are ultimately subsumed by her ‘maternal instinct’. However, one could argue that it is not an instinct at all, but a conscious choice on Indu’s part to change the definition of family to be inclusive of those who have traditionally been left out of it. Indu chooses to acknowledge Rahul and this is what gives him legitimacy. She chooses to love him, opening up her heart and home to make space for him, regardless of the circumstances that brought him into her life. The maternal love here is wilful, not a default, making it all the more meaningful. This departure from a diabolical stereotype and the vision of a truly modern Indian family makes Masoom more heart-warming than any fairy tale.